One of the things that gets repeatedly drummed into a learning writer’s brain is “Show don’t Tell.” If you’ve taken a writing class, or read a book about writing, or even inhabited the same coffee shop with other writers, surely you’ve heard this adage.

On the off chance that you haven’t, let me briefly explain: The fear (and often reality) is that the novice writer will explain or reveal too much of the story through exposition, versus showing the story through action, description and dialog.

It’s a valid concern. I think it is safe to say that most beginning writers do this. After all, it’s easier to tell in a sentence, “Bob’s true love died, and he was heartbroken” than it is to show in paragraphs, even chapters, Bob spiraling into depression and despair. Often we are writing fast, trying to get ideas down on the page, and we tend to summarize, and that looks like telling. So when writing teachers get our first drafts, these drafts are full of tell. And showing is vital for reader engagement. I don’t want anything I’m about to say to downplay the importance of revealing the story through action and description.

The pitfall of this stress on show don’t tell is that students of writing become terrified of anything that vaguely resembles telling in their work. At least, that was the effect it had on me. I tend to take feedback literally, and after being told over and over again to show don’t tell, I was producing drafts with basically no exposition at all.

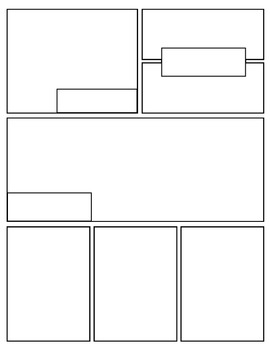

The problem with that is that you need exposition in story. Sometimes, you do need to tell. Exposition is like the text in the little rectangles on comics. It’s not a picture, and it’s not a speech bubble, but it can make the difference between a comic being a random series of pictures and a cohesive story. Like topic sentences in an academic essay, it knits together the examples, evidence and anecdotes that support the ideas. It explains and clarifies the meaning in the writing.

As a writing tool, it also serves these vital functions:

- Brevity

- Emphasis

- Suspense

- Time Travel

- Info-Dump

It probably serves a few other functions as well, but those are the ones that stand out for me when I’m writing. Don’t worry, I’m not going to write four more blogs, one on each of these points, although it’s tempting since it’s ten o’clock at night and I started this day pretty damn early. Instead, I’ll try to be succinct.

1. Brevity: You can’t actually show everything. For example, say your hero has an uneventful journey from Homevillage to Bigcity. If you show this uneventful journey, how boring will it be for the reader? On the other hand, if you tell the reader “Bob left Homevillage early in the morning and arrived at Bigcity late in the afternoon, hot and dusty from the road,” you’ve bypassed the whole problem. Sure, you’re telling, but you’re serving a purpose. Anywhere you need brevity in your story, where something doesn’t warrant paragraphs of detail but can be quickly explained or summarized to keep the reader moving through the story, exposition is your friend. But beware–if something important did happen on that journey, we do need it shown.

2. Emphasis: There are some things so important that you can’t just show them. You may want to state them clearly through exposition, then show them in scene, then tell them again. Or some combination of showing and telling. Most readers, as you may have figured out by now, aren’t exactly the brightest bananas in the bunch. Elements of your story that are crystal clear to you might not be as apparent to them. So you have to repeat yourself a lot. If you remember yesterday’s example of Robin Hobb’s “The Assassin’s Apprentice,” she ends the first chapter with the statement (telling us) that the main character is a Catalyst. Then she proceeds to show him as a Catalyst throughout the book, and occasionally she circles back and tells us again that he’s a Catalyst. As a result, the reader is completely willing to suspend disbelief when events occur later in the book that could only have happened if the main character was a Catalyst. So, if something is really, really important, tell us, show us, and tell us again, as many times as it takes for the reader to internalize it.

3. Suspense: One of the biggest errors I’ve made as a novice writer is to confuse surprise with suspense. Surprise is when a major action in the plot happens out of the blue, with no preparation. Suspense is when the reader is avidly awaiting a major action in the plot–they might not know exactly what it is, but they know it is coming. If you want your readers turning pages, you want suspense. One of the best ways to build suspense is through exposition. If you tell your reader a key bit of information before the action, they will be awaiting the action on the edge of their seats. Consider, for example, what a surprise it would be if Bob rounded a bend in the road on the way to Bigcity and encountered a dragon. Now, if this were the reader’s first encounter with dragons in the story, they would have no idea what to expect. Is it a nice dragon? Neutral? Mean? We just don’t know. The result is mild curiosity, not burning concern for the character. Now consider if the story had begun with the line “Bob had heard rumors that a particularly hungry dragon was seen patrolling between Homevillage and Bigcity.” Now, on his entire journey, we’re wondering when he’s going to round the bend and come upon a hungry dragon. That is suspense, created with a single sentence.

4. Time Travel: Another huge advantage of exposition is that it allows you roam around in time within a scene set in one timeframe. Consider the example above; Bob may have heard the rumors yesterday, but rather than having to flashback to a scene wherein Bob is in conversation with a few other guys at the village tavern, the writer can simply tell the reader that there are hungry dragons about. You can go back in time with exposition, and you can go forward, as in “The Assassin’s Apprentice” where Hobb says, ” And a Catalyst I would be.” You can reveal hints of the future to the reader, which can be key for building suspense. If you were to attempt this kind of time travel without exposition, you would end up with bulky and confusing flash-backs and even worse, flash-forwards.

5. Info-Dump: The final way I like to think of exposition as is the place where I get to infodump. Now, I’m using the term infodump kind of cheekily here. I don’t really mean to say that the information revealed through exposition can be bad writing, long paragraphs of technical explanation, or totally out of place in a scene. However, if there are certain things that just can’t be revealed in the action of the story, you have my permission to reveal them with exposition. Consider, again, the example above with Bob and the dragon. If I were to write a tavern scene where the men are discussing rumors of Dragons attacks, it could get infodump-y fast. To avoid a dialog infodump and convey the same information, I could write a scene showing someone previously getting attacked by dragons on the way to Bigcity. Which is a possibility, and some writers will do this sort of thing. But say my book is limited to Bob’s POV. I can’t show an attack that he isn’t witness to. I have to dump in the information somewhere. Exposition is the only place to do that.

Well, that’s about all I know about exposition. What do you think? Did I miss any uses for it? Does anyone disagree or have you had a different experience with Show VS Tell? Let me know in the comments!

Tomorrow (God willing) 101 TIWIK #7: Description: Borrow from Artists to Paint Your Picture with Words.

This post is part of a series of 101 Things I Wish I’d Known Before I Wrote My First Book. Start reading the series at the beginning.

One thought on “101 TIWIK: #6 Pssst–It’s OK to “Tell””