Hi there, welcome back to 101 Things I Wish I’d Known Before I Wrote My First Book! It’s been awhile since I’ve posted, but I’m back in the saddle now, and ready to move on to the revision stage of writing.

Just a quick recap before I dive in: We’re in the middle of a miniseries on the stages of writing. I’ve already covered drafting, hiring an editor, and rewriting. I have yet to cover revision, line editing, copy-editing and proofreading. Today’s post starts a three part series on revision. In this post, I’ll share my answer to the question: what is revision? The next post will pose a series of questions to consider about your draft when assessing its revision needs. Finally, I’ll cover some strategies for an efficient and effective revision pass.

Before I define revision more clearly, I want to reiterate something I’ve said in earlier posts about the stages of writing. These stages, listed above, are not linear. Not every writer writes a draft, then rewrites it, then revises, then line edits, and so on. Very often, I’ll find myself making minor copy edit changes at all stages of the writing process, or revising a scene before I’ve determined whether I need to rewrite the whole draft.

There’s nothing wrong with taking the writing stages out of order. In fact, sometimes it can be very necessary to the creative process. But if you can do them in order as much as possible, you’ll find the process is more efficient. There’s nothing more frustrating than revising a scene to perfection and finding you have to throw it out because it doesn’t fit in with your rewrite plan. Or trying to do revisions in the proofreading stage that introduce error so that you have to go back and line edit and copy edit all over again. For this reason, it’s best to try to approach your draft from a large to small perspective–make larger changes first, then narrow down to smaller changes.

So how will you know when your draft, whether fresh off the printer or heavily rewritten, is ready to revise? If you remember from the posts on rewriting, rewriting is largely about finding your story and getting to know your characters.

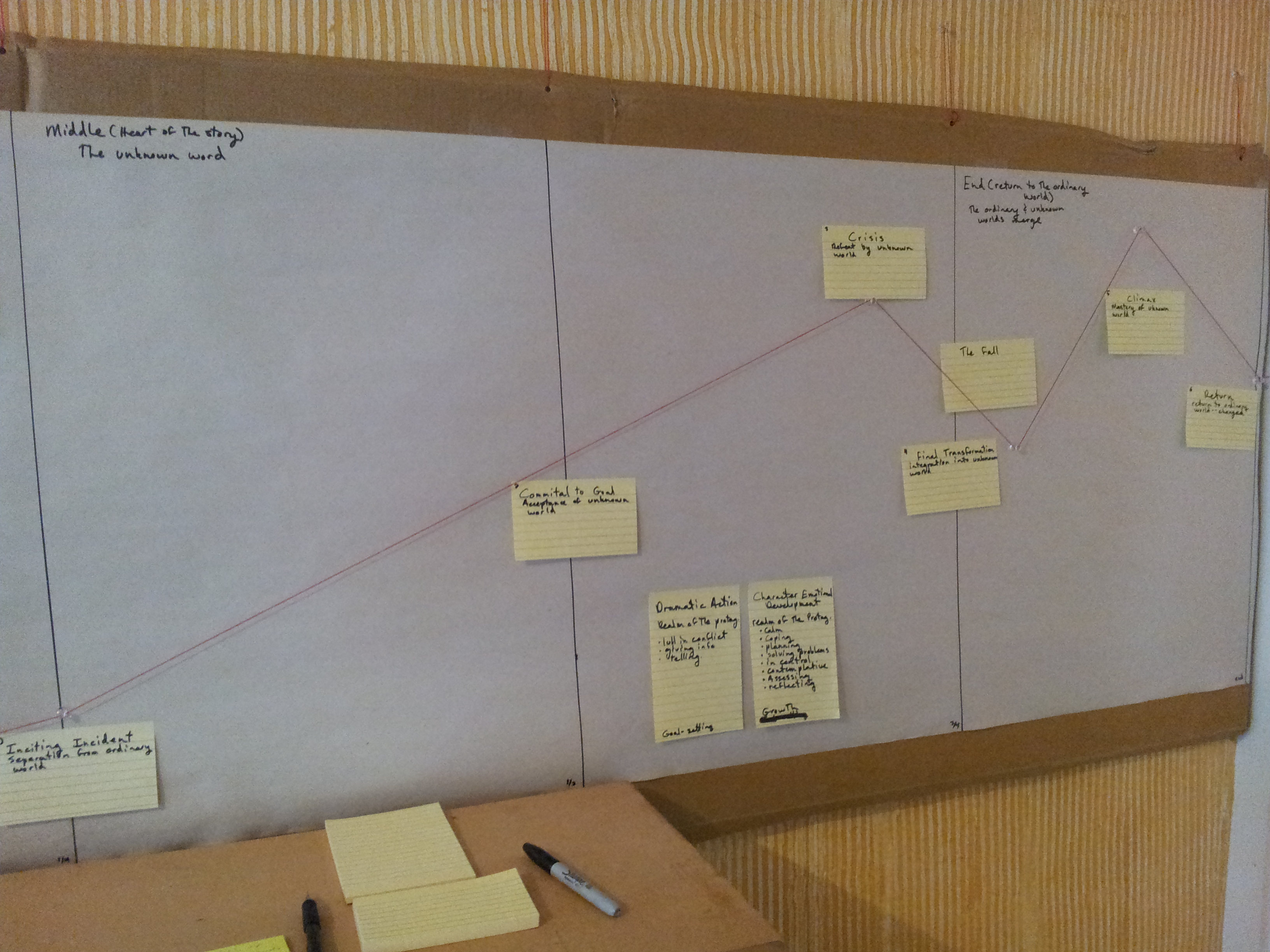

Revision, conversely, is a step to take when you have the shape of the story clearly laid out in your mind, in your plan, or, if you are lucky, in your draft. Revision is about taking the story that you have established in your mind and making your draft match to it as closely as possible. When I say story in this context, I mean every part of the story, from the setting and theme to plot and characters.

While rewriting should have moved the words on the page much closer to the ideal in your mind, there’s a good chance you have a lot of revision to do before these two different things actually touch. How do you know how much revision you have to do?

Ask your peers. This is often the very best stage at which to share your writing with other writers. They will be able to tell you if that character you intended to be sympathetic and angsty is coming across instead as a spoiled brat. They will be able to tell you if your plot is confusing because you, the writer, understand that the hero hates his father, but you haven’t expressed that on the page. They will be able to tell you your villain is coming across as one dimensional, even though you know she’s secretly tortured with grief. They will point out which parts are too slow, which parts are emotionally flat, and so on and so on.

But, and this is a big BUT, you cannot rely solely on peer readers to point out these flaws in your draft. The more drafts and novel length projects you work on, the better you need to be at recognizing these discrepancies in your own work. For two reasons: firstly, the more closely in line with your story ideal the draft is before you share it with others, the better, because they will be able to help you get it even closer. Second, reading is a highly subjective activity, and chances are if you hand six different people your manuscript, you’ll get six very different opinions on what you need to change. It can be easy to get lost in all these different voices, or even just derailed by one strong voice, and lose sight of your own vision for the story.

Consequently, it is really important that you not only have a strong vision for the story but also an ability to look at the words on the page and make a clear judgement about how far or close your are from that vision.

In the next post, I’ll pose several questions you can ask yourself when assessing the revision needs of a draft, examining plot, character, setting and theme. Stay tuned for 101 TIWIK #60: Revision Questions.

Just a quick reminder that Dream of a City of Ruin releases March 20th and is now available for pre-order! If you intend to purchase a copy directly from me please pre-order so I will have the right number of available copies on March 20th! If you are local I will hand deliver : ) Thanks so much!