One of the questions I get most frequently from readers is, “how do you come up with all the names?”

It’s a hard question for me to answer, because it tends to vary quite a bit.

When you’re building a world from scratch, not only will you need unique character names (nothing wrenches readers out of your fantasy world quite as fast as a knight in shining armor named Bob), you will also need names for all the places, creatures, titles, concepts, etc.

That’s a lot of names.

Not only is it a lot of work to come up with all those names, it’s also absolutely crucial to reader enjoyment. The right name can change the whole feel of your story. For example, think of the names in the Lord of the Rings. The hobbits all have a certain kind of name. Bilbo, Frodo, Pippin. If Tolkien had been writing poetry, the hobbits would have been a cheerful, merry poem. Then consider the names of the elves. Arwen. Elrond. Glorfindel. Their names sound like running water, or wind. If we were to encounter an elf named Pibbo, we’d have entirely different expectations for him than we do of the lofty creatures of Rivendell.

Names, both of people and places, should vary in different regions and cultures of the story world. In fact, this can be a great way to make your cultures seem distinct. The other side of this coin is that names should be consistent within the region or culture in question. Random names that don’t fit should have a reason behind them.

Names should also match the feeling you want to convey about a people, culture, place or concept. Give a villain an ominous name. Give a sacred place a solemn name. Give the rough side of town a gritty name. Give the beautiful young love interest a name that tastes like sweet wine on the lips.

Play with syllable count

Consider the different effect that different word lengths produce. One syllable words make a short, sharp, firm sound, like one beat on a drum. Tat. Pip. Mon. Fren. The implication is one of a simple person, or perhaps a primitive culture, or of names so familiar that they’ve been shortened to their root, like nicknames among close friends.

Now compare that to words with two syllables. Tatten. Piple. Mondar. Refren. The sound is completely different. Words with two syllables are common and comfortable. They are easy to read and pronounce. They are probably the words you’ll use most often.

Add another syllable. Tattenren. Ispiple. Mondarelle. Refrenush. See how it changes the feel yet again? Now the word has texture, and the feel of each word is very distinct. Three syllable words are like miniature songs. In my opinion, they serve best to convey a sense of importance, like a legendary place or a monumental person.

What happens when we add a fourth syllable? Tattenrenzene. Ispipletle. Urmondarelle. Refrenushar. The words become unwieldy, difficult to read, difficult to pronounce, difficult to recall. Unless you have a very good reason to do so, I recommend keeping most words in your story world to three syllables. Save a four syllable word for something you need to be absolutely distinct and important. And, if you can, give the reader a shortened nickname for the thing to make the word easier for them to recall.

Whenever you create a new word, read it aloud. Think about how it sounds, how easy or difficult it is to pronounce. Remember, the point isn’t to make things difficult for the reader.

In your eagerness to make certain sets of words in a region or culture sound similar, don’t get caught in the smurf trap. Vary your invented words enough so that you don’t end up with everything sounding like a variation on the exact same thing.

So how do I come up with my names?

Sometimes I get really lucky. Sometimes they just come to me, the perfect name appears and it fits the place and time and works. The name of Glace, Stasia’s bodyguard, came like that. That happens maybe ten percent of the time.

The other 90 percent, here’s what I do:

First, I always give the thing a working name. The working name could be as simple as the real world name for a similar thing, or it could be a crappy made-up name. It keeps me from getting slowed down in the drafting process by obsessing over what to call the thing.

When I finally decide I need a real name (usually close to the end of the drafting process) I examine the thing. What is the idea behind it? What is the feeling I want readers to have when they encounter the thing in the story? Then, I look for a name in the real world that matches the thing, the idea, or the feeling, or all three if possible.

Sometimes the real world name comes easily. For example, when I was looking for a name for the bad guys that kill people by turning them into dust, the obvious real-world name to start with was dust. Othertimes, I have to search. For example, when considering a name for a female villain, I looked up a list of names of goddesses, searching for one that was particularly evil.

Then, I take the real-world name and twist it.

In order to twist it, I usually look up the word in other languages, or use etymology.com to find some older versions of the word. Usually I find a way to change the foreign or ancient word to fit the thing in the story.

For the dust-guys, I found that a Sanskrit cognate for dust was dhu. The word dhucir sprang to mind, but two syllables didn’t really sound right for these truly epic bad-guys, so I lengthened it to Dhuciri, which sounded dark, mysterious, and little bit mafia-esque.

Once I’ve come up with that perfect name, I ALWAYS run it through a google search. You’d hate to find out that it’s been used, or that it has real world connotations you don’t want in your story-world. Here’s a fun example of how that happened to me:

When I was crafting the underground story world of Dream of a Vast Blue Cavern, I came up with a clever way to shorten the words Stalactite and Stalagmite: by calling them stalac and stalag.

Stalag, my writing group was quick to point out, was a German term for prisoner of war camps. That was something a quick google search would have revealed. So no matter how tiny a part of the story world, always run a google search.

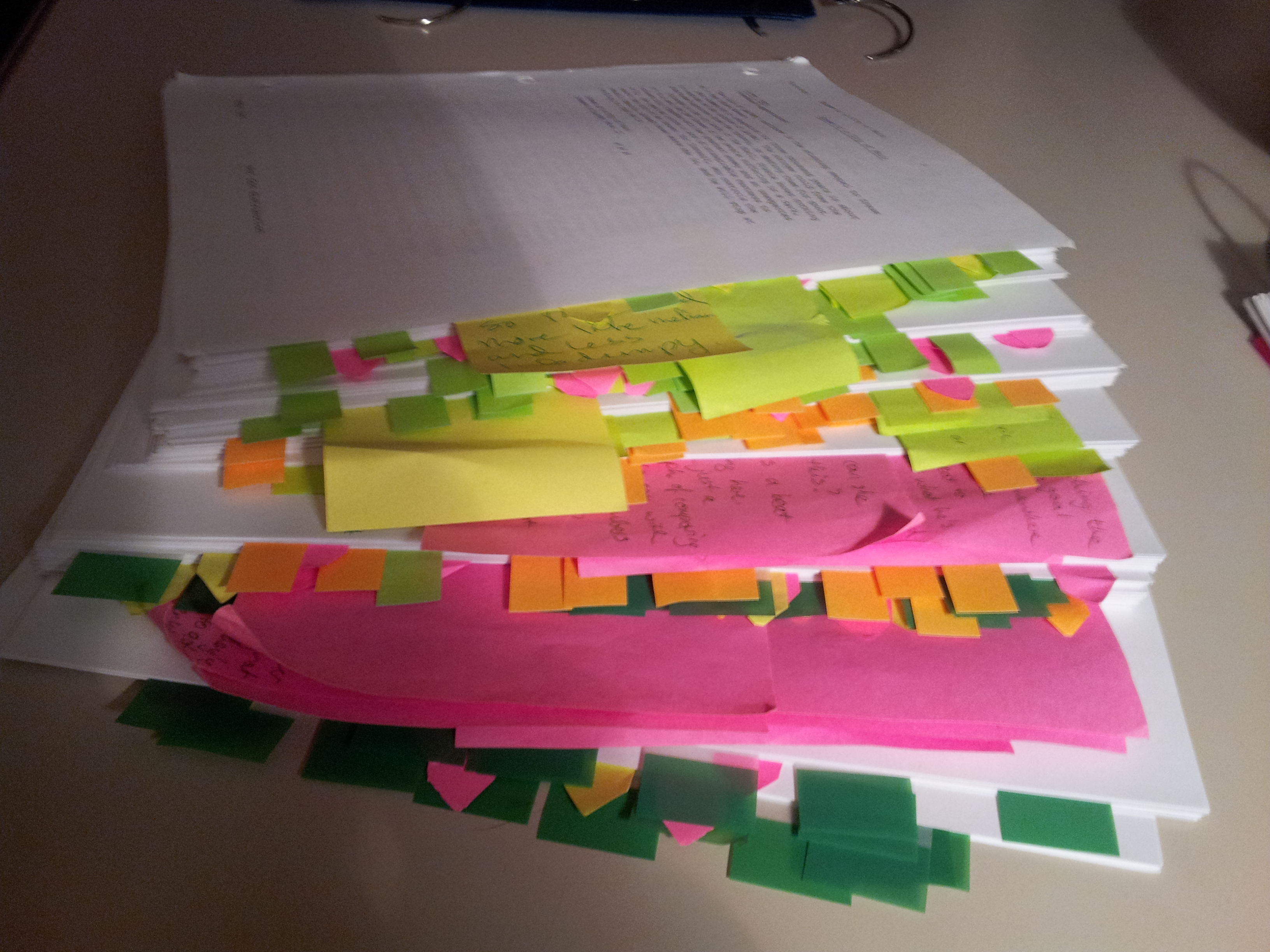

Once I have the final name I’m going to use, I use Find and Replace to change the working names to the final ones. But, be really careful put a space after the word you intend to replace in the Find field, because if that word is a component of other words, it will replace it wherever it finds it. For example, if you’re replacing Nam in this document with Namaram, you could end up with “Once I have the final Namarame I’m going to use” sprinkled throughout the document.

That’s just one way. It’s one part luck, one part skill, one part invention, with perhaps a dash of superstition. How do you come up with names?

Next week we have a treat: a couple of guest posts from fellow authors familiar with the conventions of researching the real world! Starting out with 101 TIWIK #37: Creating Historical Worlds with Janet Oakley. Have a great weekend!

This post is part of a series of 101 Things I Wish I’d Known Before I Wrote My First Book. Start reading the series at the beginning.

If you’re enjoying this series, please sign up for my email newsletter for a monthly update on appearances, book releases, giveaways, special deals, and a blog round-up!

One thought on “101 TIWIK #36: Fun With Names”